|

The first of the "four noble truths" of Buddhism is dukkha, or suffering, disappointment, discontent. Psychologist Carl Jung said, "There is no consciousness without pain." It isn't hard to sit in meditation. What is difficult is what we notice about ourselves, the stuff we'd rather not look at.

But Buddhism starts off with the message to pay attention to the hard parts. Meditation is not an escape. Instead, it is the discipline to sit with everything, with joy and sorrow. It is the wisdom of the middle way: not wallowing in pleasure, but not wallowing in self pity either, Suffering is a teacher. Inherent in suffering is already the knowledge of something else. Inherent in sorrow is the joy having known something or someone. To go through sorrow is to discover that joy has never left. Joy and sorrow, life and death, in-breath and out-breath: such 'dualities' inform each other. They exist in relationship. If we try to have all of one or the other, the result is suffering.

0 Comments

Commentary by Gendo

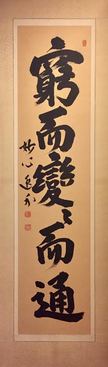

What does it means to practice Zen? After sitting in a peaceful Zendo, you and I have to return to a world where people do not understand, to a family that is loud and busy, to a driveway still surrounded by snow. How do we figure out the connection between practice and everyday life? If we don’t do that, meditation is small and idealistic. These days, everyone is into mindfulness meditation. In hospitals they say it is good for your health, in business they say a mindful worker is a better worker. All that may be true, but mindfulness meditation with some goal in mind is not true mindfulness. Mindfulness is fullness of mind and mind includes everything: it includes the peaceful zendo and the dirty snow, kind people and nasty people, good days and bad days, healthy people and sick ones. Sitting quietly may be useful training, but the practice is everything we do. An old teacher said, " if you are going to cultivate immovability, when you see people simply do not see people's right and wrong, good and bad, faults and problems; then you own essential nature is unmoved." My Zen teacher used to say: “You have to swallow God and the Devil!” He also said, “Everybody wants to go to heaven. But you can’t stay in heaven. There are no toilets in heaven.” In other words, don’t get stuck on perfection. Don’t just transfer your greed to some spiritual ideal. In the Hearts Sutra, we chant, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form”. Buddhism teaches that there are two truths: absolute truth and the relative truth of everyday life. Both are true. Watch out! Neither one can be fixated. Meditation practice is about seeing things truly. Our Western culture came up with science in order to know the truth In India the truth problem was seen as an inside job: how do we know the world as a matter of conscious awareness? What gets in the way of our happiness, what causes confusion? Both science and Buddhism conclude that to see clearly you must be detached. You have to set aside personal preferences. In science they call it “being an objective observer.” If you test drugs and are paid by the drug company, no one will trust your results. In Buddhism we say “take an attitude of neither indifference nor attachment towards all things.” In order to ski down a steep hill successfully, you have to see things clearly. You have know what it means to do that well. But you also need to know what it means to crash. If you get too excited about success, you will underestimate danger. The middle way, wisdom or equanimity, holds both success and failure. So when you sit in meditation or what we call zazen, sit without preferences. No preferences! Sit with no preferences and know the fullness of your own mind. Commentary by Gendo This calligraphy by Kajiura Itsugai, former head of Myoshin-ji temple in Kyoto, Japan, hangs in our Zen Center. It was a gift of Kyonen Jim Gordon, a friend, mentor, fellow practitioner and lay ordained Zen monk. It is a quote found in the Blue Cliff Record, an ancient collection of koans, cases used to test understanding. What does this mean? One way or another, we are reaching an extreme, coming to an end, all the time. How does a person pass through? How do you live your life in the midst of change? Sometimes a big change comes along: Someone you love dies, or a relationship breaks up, or storms destroy your home, or (before long) carbon tax makes your car unaffordable; and you think, something has ended that will never happen again. Nothing I do will change this reality. How do you “pass through”? I write this at the end of the year. We will never see the year 2018 again. For better or worse, it has come to an end. Buddhist tradition explores change with attention to a basic, embodied activity – breathing. Breathing repeatedly comes to an end, reaches an extreme. Breathe out and you reach a point beyond which you can go no further. Then what? After a moment’s pause comes change, transformation, and the opposite activity, in-breath, takes over. Human beings have evolved consciousness to further their own situation. We have learned, and teach our children, to identify all kinds of objects, to know likes and dislikes, and to form an idea of self, of who I am. But Zen points out that consciousness is imperfect. It is imperfect, because everything we identify as an existent thing, including ‘self,’ is subject to change, to impermanence. They do not last and that which does not last we experience as beyond our control; and what is beyond our control, we understand to be other than myself. Everything we are taught to name and know reaches an extreme, comes to an end, regardless of our intention. If even ‘self’ is not ‘mine’ to control, where am I? Who am I? These are existential questions, the suffering, inherent in consciousness – the ‘tree of knowledge’ that Adam and Eve discover in the Garden of Eden. Buddhism teaches that the reason human consciousness is imperfect is that knowledge is an act of discrimination. We discriminate in-breath from out–breath; which is to say, we know one because we know the other. What is imperfect is the assumption that, because we have named them, each has it’s own essence, its own independent existence. On inspection, however, that assumption is mistaken. It is delusion because in-breath and out-breath, like all objects of consciousness, are discriminated, one in relation to another. The larger truth of breathing and all objects is not separateness but relationship, activity empty of separate identity, beyond conception, beyond thought altogether. That reality, like breathing, is dynamic, never fully one thing or another. It is the ‘cosmic dance’ that cannot be objectified, and yet neither is it 'nothing.' Consequently this ‘non-object’ is personified as God, or Dharma, or ‘true self,’ or true (selfless) love. How do we know such a truth? There is no object to be acquired or taught, no self to attain it. It simply is what is experienced when the mind that fixates object and identity is quiet; as in the stillness at the extreme between in-breath and out-breath, a stillness empty of distinctions, self and other, and, at the same time, all-inclusive. Potluck Lunch. Join the Board of Directors for potluck lunch, January 6, 11:30 to 1:00 at the Zen Center. All are welcome. Bring something to share. Let us know if you plan to come. December Theme: Inclusiveness/Patience Inclusiveness, or patience and ‘forebearance,’ is the second of the “paramitas” of Buddhism. The word ‘paramita’ comes from ancient Sanskrit language meaning ‘perfection’ and ‘having reached the other shore.’ Paramitas are like boats, or bridges over ‘troubled waters,’ reminders of what helps in hard times. In the cold and dark of winter, the reminder is to share, not hoard, to reach out and invite the stranger in. The stranger is, after all, your self, the one who got used to summer sun and now struggles with snow boots and shovels. Welcome the stranger! Because generosity and inclusiveness lead to something bigger, something capable of joy. Retreat! December 8 is ‘Rohatsu’, celebration of the Buddha’s awakening, marked with renewed resolve and practice. Our Rohatsu retreat begins Thursday, December 6, 8 am at Moose Mountain Retreat, a house generously offered to us, a half hour drive from both downtown Hanover and Lebanon. (People are welcome to arrive the night before, December 5, after 7 pm. ) Registration closes the end of Sunday, December 2. ‘Intro to Zen on Wendesday, December 5 is cancelled. Also Study Group December 6. Sunday practice, December 9, will be held at Moose Mountain Retreat (inquire for travel details). Also, see retreat page here. Family Zen This month (November) at the zendo our theme has been Generosity. In keeping with this theme, the Family Zen Group is planning to visit the Haven in White River Junction on December 28th for a tour and as an opportunity to donate some of the items which they have indicated are needed. We will package the items in individual bags along with a wonderful drawing or greeting which our Family Zen group recently made. If you would like to join in this effort, please consider donating something from the list below. We will leave a box at the UVZC, outside the interior hallway door, where you can leave your donation, whether or not we are open. Here is the list: o Gloves or mittens o Snacks -such as granola bars, small bags of nuts, crackers and peanutbutter o Small travel size shampoo, toothpaste, hand lotion, toothbrushes, Chapstick o Small combs and brushes o Water bottle o Warm Socks o Notes or drawings of encouragement or greeting We have already received a great discount from Hanover Hardware Store for a case of foot warmers, which we will include. Thank you for your interest and support in this project. Please let us know if you have any questions. Have a wonderful day! Shinji Patty Goodman and Jing Mayer These are pictures from Gendo's November 25, 26 trip to Dai Bosatsu Zendo, a gathering marking Dharma transmission granted by Shinge Roshi, abbott of the Dai Bosatsu, to Kyo-on Dokuro Jaeckel. The event was attended by Shunan Noritake Roshi of Kyoto Japan and abbott of RInzai-ji in Los Angeles, marking a new era of connection between Rinzai-ji and Dai Bosatsu, two branches of Rinzai Zen practice in the United States. Click here to see the album of photographs from the sesshin.

MIND AND EMPTINESS |