|

Commentary by Gendo

“As to performing the six paramitas and vast numbers of similar practices, or gaining merits as countless as the sands of the Ganges, since you are fundamentally complete in every respect, you should not try to supplement that perfection by such meaningless practices. Huang Po Ancient Zen teacher Huang Po, says performing good deeds with intention of becoming a Buddha is a waste of time. Not that meditation or ‘good deeds’ are the problem. Rather, it’s about effort. Who’s trying to do what to whom? Meditation is paying attention to what is already here. To notice what our own body and mind, what experience teaches us. Is all this Zen stuff really necessary? No! It’s only because we lose our way, that practice is established. It is, of course, by our senses that we engage the world of our experience. All experience begins with raw sensory perception, empty of distinctions (form). Then feeling arises, feeling that leads to a perception, to an intention, and to consciousness of an object and of the “self” that observes it. That sequence of events, called “skandhas”, describes how wrapt, selfless attention, empty of separate identity, breaks apart and becomes “self” and “other.” The transition from wrapt attention to “I am here” and “it is there,” is, in most cases, instantaneous. It’s our human nature to a focus on self and other, from the standpoint of self-interest and self-protection. But, sooner or later, self protection fails. Change (shit) happens, and we suffer. Once in while, a powerful moment of wrapt attention lingers, and we say, “It took my breath away;” a moment expansive , joyful, without fear, empty of self- consciousness. Then the question arises, “How do I get back there?” But it turns out that “I” can’t get there. Because, in that moment of selfless absoption, “I “ wasn’t there! Something like letting go of “I” has to happen. Like trying to remember something, and the harder you try, the further you get from it. But stop trying, do something else entirely, and all of a sudden, you remember! Like breathing. Forget it and it just happens. Breath is poetry for how consciousness works, how the discriminating self arises, and how self disappears in a moment when mind is at peace. Breath has two dimensions, explained in my Zen training as expansion and contraction. Outbreath is expansion, releasing what was held inside, expanding until it can expand no more. Then, for a moment, outbreath and inbreath rest together. Then contraction, in-breath, wakes up, drawing in all of outside, until it can contract no more. For a moment, it rests together with out-breath. Then expansion wakes again and seeks its home. Inbreath and outbreath constantly function relative to each other, like countless other opposites: day and night, male and female, life and death to name a few. All are distinct, opposite activities, generalized as expansion and contraction; and, at the same time, each is constantly changing and together are one whole: you can’t have one without the other. Between moments of rest, expansion and contraction separate, one active, the other quietly in the background. When expansion and contraction separate, space opens up between them. From this space discriminating consciousness is born, the self is born that discriminates between expansion and contraction, discriminates one thing from another from the standpoint of its preferences. When expansion and contraction rest together, they are one unity. Then the space between them disappears, then the consciousness that is self disappears. But of course, inbreath and outbreath, expansion and contraction, are always one unity, one activity. You can’t have one without the other. This is the case when they meet and come to rest together. It is also the case when they separate, giving rise to the self that disitnguishes one from the other. One becomes three. Three becomes one. We have lived experience of an “I am” self. Look carefully and we find that ‘self’ is constantly being born and disappearing in moments empty of self. And, as breath demonstrates, even in moments of discriminating awareness, inbreath, outbreath and self remain one whole. Rather than another “I am” project, something to be achieved, precepts are the reminder of who we already are, where this “I am” self comes from in the first place.

0 Comments

Summer Solistice, 2024, includes the full moon - maximum sun, maximum moon! These moments of solistice, both expansion and contraction, get our attention - especially December’s contracting sun, as in Christmas, Buddha’s birth, Hannukah and others.

There are many teachings, Buddhist and otherwise, surrounding such moments. But, of course, it comes down to experience, yours and mine. Contraction and expansion, the interplay of opposing activities, are happening all the time: day and night, in-breath and out-breath, male and female, life and death Consciousness itself is made possible by the contrast of one to another. And, like day and night, together they compose one dynamic whole. But it seems human nature to get caught up in one side or the other of such dualities according to our preferences. Change happens, inevitably, contraction and expansion happen, and we suffer. Mind is like a house with closets where we have hidden troubles we try to ignore in hopes that they will go away. We all do this. But, of course, they do not go away. In subtle ways, they continue to influence our moods, our interactions, even our health. In fact, trying to avoid and suppress them only reinforces the disturbance! The question arises, “How do I quiet my mind!” Sometimes something wonderful happens, a startling sight or sound, an expansive moment of wonder and joy. Afterwards we think, how can I get back to that moment. But try as we might, we cannot get there. Try to recreate the situation and it isn’t the same. The question arises, “How to get there?” In both cases, the irony is that “I” can’t get there. “I” can’t quiet the mind. On reflection, in those moments of joyful abandon, “I “ wasn’t there in the first place! Apparently, something like letting go of “I” is necessary. But that is hard, scary even. What does that letting go look like, what sort of “diligence” is required to get there? Because of such questions, practices, like Zen, like the spiritual quests of all cultures, become established., Zen is discipline to study the world of our experience, how our minds work, how consciousness works; the study of expansion and contraction, just what’s happening. Breath demonstrates that expansion and contraction naturally seek their homes, seek completion, where both rest. Outbreath expands, releasing what was held inside, expanding until it can expand no more, when, for a moment, outbreath and inbreath rest together. Then in-breath wakes up, drawing in air, contracting outside until it can contract no more. For a moment, it rests together with out-breath. Then expansion wakes again and seeks its home. Between brief moments of rest, expansion and contraction separate. One is active, the other quietly in the background. Zen tradition explains that when expansion and contraction separate, space opens up between them. It is in this space that the consciousness emerges that that discriminates between expansion and contraction. And the one who discriminates is, of course, the self. When expansion and contraction rest together, they are one unity. Then the space between them disappears, the consciousness that is self disappears. Breath is poetry for understanding how consciousness works, how the posture of a discriminating self arises, and also how moments rest and peace of mind are moments free of the preoccupations of self identity, free of object fixation and discursive thought. Breath is poetry for “Buddha nature,” embracing the big picture, both expansion and contraction, both their completion and their separation. Or, as is said, awakeniing, to “unity, diversity and impermanence.” * In the words of Nisargadatta: “When I look inside and see that I am nothing, that is wisdom. When I look outside and see that I am everything, that is love. My life turns between these two.” * Joshu Sasaki’s interpretation of “dharmakaya, sambhokakaya, nirmanakaya Commentary by Gendo

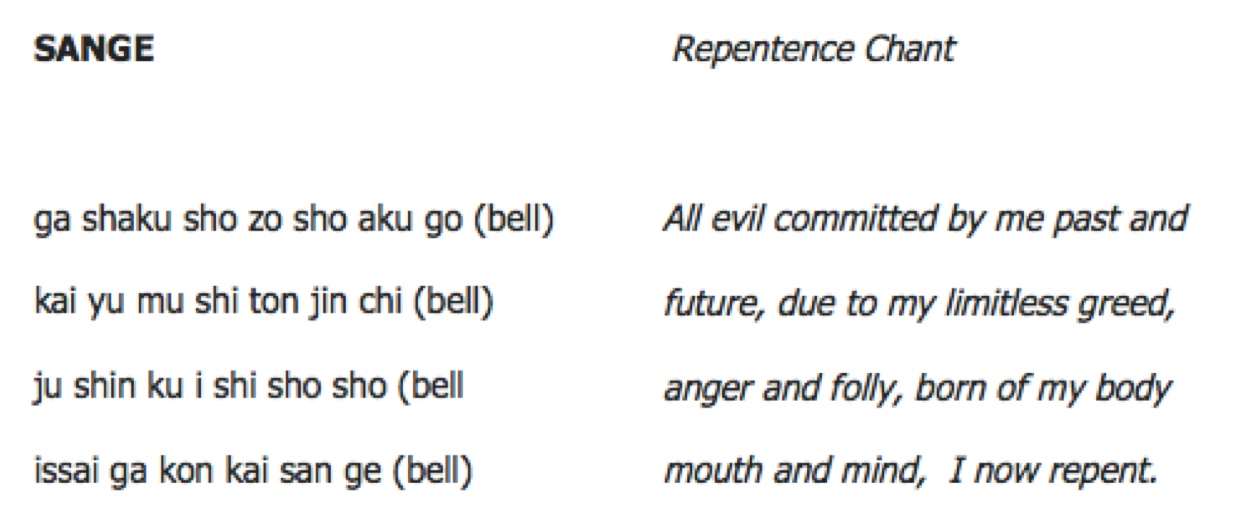

TEXT: “Your present thoughts and actions are the product of you past thoughts and actions. Likewise, your present thoughts and actions will produce your future karma. What can give a new direction to the mind and its karma is your present thoughts and actions. Through the repeated practice of samadhi, the old trend of the mind is slowly changed. This is “redeeming your karmic debt.” (Katsuki Sekida) “Karma” is a word vaguely associated with such ideas as ‘reincarnation,’ past and future lives, ideas rational Western minds struggle with or joke about (“your kama hit my dogma!”). But maybe it helps to recognize that we have stories equally mysterious in our Westeern culture, as in “A Christmas Carol” where Scrooge contends with “the ghost of Christmas past.” Then there are such phantasms as the overweight Santa who presumably squeezes down our chimneys, not to mention the the “God” mystery worshipped in churches everywhere. I suggest that God, Ghosts and Karma personify an aspect of human experience beyond our default assumptions of reality as material presence. Like the stone that sits on my dresser, the reincarnation of a memorable walk on a beach. My Zen teacher spoke of Karma as “the activity of impermanence.” The image that comes to mind is a river. A river flows on in a constant state of impermanence, which is not an issue until you try to plant your feet midstream. Then you end up fighting against the current. Then Karma becomes an issue. People speak (as in our text today) of creating or producing karma. But impermanence is already here. It is our standing in opposition to impermanence that creates conflict, that creates karma as a matter of awareness. In other words, to make an object of some thing, to seize on some situation or thought, to fixate what is, fundamentally, impermanent, is to plant our feet in opposition to the rushing tide of karma, of impermanence Then past action leads to present and future conflict; what we might call “karmic debt.” I suggest “repentance” begins with paying attention to “karmic debt,” noticing the stance taken, the feet planted in the past, that has led to conflict. And, of course, it is this noticing that is the first step to doing something about it, noticing that is the discipline of a Zen practice. And what can be done about “karmic debt,” about those fixations. Sekida says, “What can give new direction to the mind and its karma is your present thoughts and actions…This is redeeming your karmic debt.” The notion of doing something about fixations of mind, about “karma,” rises up quite naturally. Not because of something you have read or what someone has said. Something inside us greets fixation with the question: “How do I quiet my mind?” In other words, we already have an inkling of something different. Otherwise the question wouldn’t rise up in the first place! Isn’t it often the case that we try to change the fixations of our minds by trying to force them away, by supressing them, only to discover that our minds just get busier than before? What have we done? And who is trying to do what to whom? I’m trying to quiet my mind? The same one that fixated the situation in the first place is trying a new fixation? Isn’t this just replacing one “karmic debt” with a new one? So what are those “present thoughts and actions” that “redeem your karmic debt?” Sekida suggests that “doing something” about kamic debt involves what he refers to as “the repeated practice of samadhi.” What does this mean? Samadhi is an ancient Sanskrit word for that rapt attention in which distinctions of “self” and “other” have disappeared. Like that instant before you have separated from and objectified the experience with words: “Oh, what a beautiful sunset.” Samadhi is a return to that source from which the problem of fixation arises in the first place, the source where impermanence is just happening, before we have stood up against it. As Joko Beck says in her book, “Everyday Zen”: “…what we have to do in Zen is … to pay attention to this very moment, the totality of what is happening right now.” The totality of now includes both our likes and our dislikes, both the singing bird and the silence, both day and night, like in-breath and out-breath, each happening in relation to the other. It is a moment of gratitude, gratitude owed to dualism, to the parents, who give birth to this consciousness, this self; a self, which, despite our fears, is not alone. The conclusion of a year is a moment of samadhi, a moment reckoning the entirety of the earth’s journey around the sun, both Winter darkness and Summer sun; reckoning the self aggrandizing of our past, the temptation to return there in the future, redeeming “karmic debt,” in the oneness of this present moment, in generosity and compassion. Commentary by Gendo (based on Zen Sunday, 4/9/23) In Spring we celebrate Buddha’s birthday. Where is the Buddha? Where was Buddha born? The Buddha, the “Awakened One” in history was born 2500 years ago in Northern India; and is celebrated for insight into the nature of suffering and its resolution, insight that remains relevant in our time. But Zen, the practice of Buddhism, is very clear on this point: Buddha/God/Truth – does not exist as an object. We search in vain if we look for a Buddha removed in time and circumstance. We cannot stand detached from that which is ultimately true. If we are to know the birth of the awakened mind, we must know it for ourselves. Zen teacher Rinzai (9th Century China) says: “Bring to rest the thoughts of the ceaselessly seeking mind and you’ll not differ from the Patriarch-Buddha. Do you want to know the Patriarch-Buddha? He is none other than you who stand before me listening to my discourse.” To know Buddha’s birth we have to get involved. To ‘wake up’ to Spring is involvement. Ceremonies and ritual are established to feel in our bodies what words and ideas cannot express. Today that ceremony starts with vulnerability, with repentance. Likewise, Spring’s glory is born from Winter fatigue. Our joy embraces the paradox that vulnerability, suffering, is its precondition. Rinzai says, “even though you have committed the most heinous of crimes, that is the ground of your enlightenment.” Winter and vulnerability are a glimpse of death, death of who you might have liked to be. But the death of an ideal self, makes possible the birth of a real self, a self that knows both life and death as its contents. And all beings are like this. The death of a discriminating self and the rebirth of a non-judgmental, inclusive self is the dawning of compassion, of true love., free of fixation on life or death; the birth of awakened awareness. Embracing the flavor of non-judgment, which is already our contents, we practice. We practice sitting quietly and still, without fixation on thoughts. We chant. Today we chant “sange,” a verse of repentance, bearing in mind that the chant itself means nothing without the conviction each of us brings to it, without the experience of unself-conscious engagement, that experience of ‘just doing’ what needs to be done. Next we will engage in the ritual of washing the baby Buddha, while chanting the heart Sutra, recognizing that in doing so, we cleanse ourselves. Wash away jealousy, and conceit, deceitfulness and greed. Wash away addiction and anger. Wash away all that confounds the simplicity of a child; a child’s whole hearted embrace of the world. I will go first and others who wish may follow.

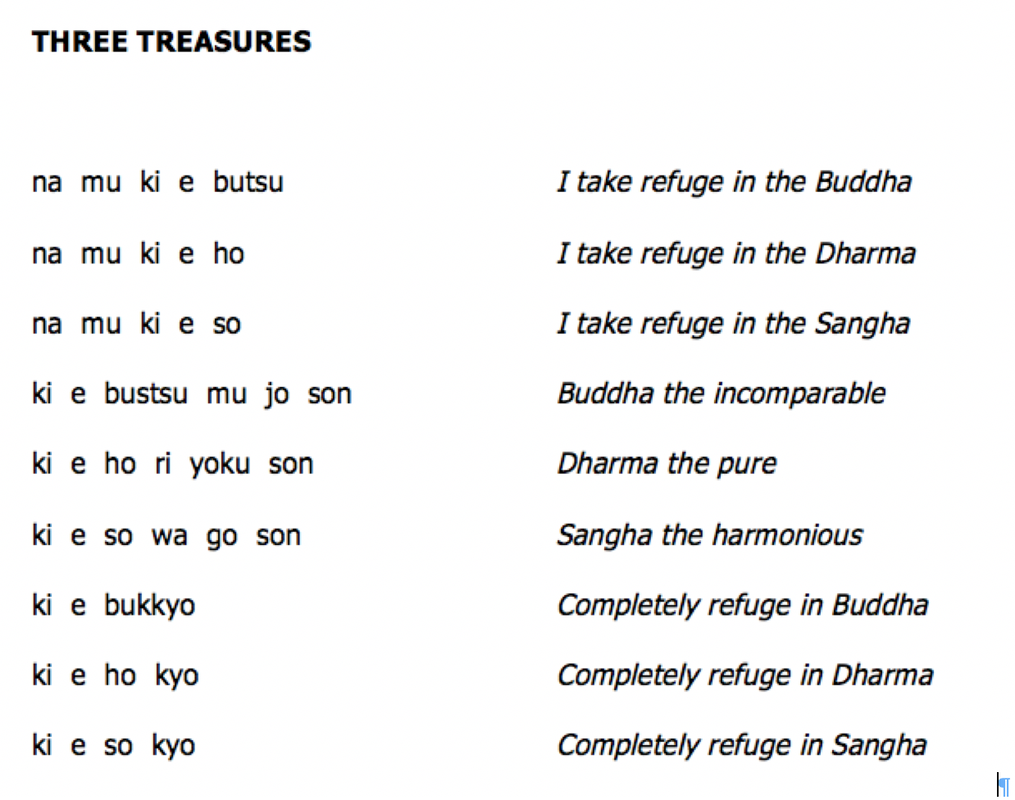

HEART SUTRA Now we take refuge, as Buddhists all over the world have done for thousands of years. Refuge is shelter from the storms of our human lives. Having enacted the principle, we take refuge in its truth, returning again and again to its shelter in times of confusion and distress. The idealized self that clings to life and rejects death disappears in the awareness that both are who I am. Refuge in the Buddha is refuge in awakened awareness. . The selfish self that clings to material objects for affirmation disappears in the realization that truth is found in the unity of self and other. Refuge in the Dharma is refuge in the teachings of our true nature. The self-absorbed self that clings to its own accomplishments, and judges the good and bad qualities of others, disappears in the realization that all beings of my perception are mirrors of myself. Refuge in the Sangha is refuge together with all beings. Lets recite the three refuges together. I take the first teaching of Zen to be what we discover for ourselves when we sit quietly and still: our own busy minds. The second teaching is what wells up inside, this question: "How do I quiet my mind?" Third, is finding that we can’t avoid or suppress our minds, our suffering, without adding to the turmoil. This, after all, is the first ‘noble truth.’ It doesn’t work to hide from difficulty. Finally, to go through difficulty is to discover the relative nature of all objects of attention, coming and going, like breath. And like breath, this ‘coming and going’ is ordinary, just what we do; like walking, one foot after another, on a path.

Gendo TEXT: “Your past lives are simply the deluded mind of your previous thoughts, and your present life is simply the enlightened mind of your subsequent thoughts. Use the enlightened mind of your subsequent thoughts to reject the deluded mind of your previous thoughts so that delusions have nowhere to cling … the moment your deluded thoughts are eliminated, the bad karma of your past lives is wiped away.” (Huineng)

"The first step of Zen practice is to manifest yourself as nothingness. The second step is to throw yourself complete into life and death, good and evil, beauty and ugliness." (Joshu Sasaki) COMMENTARY January, 2023 (Gendo) There is something natural about repentence at the start of the year; a time to survey what has gone before, to evaluate all that you have left behind, and then to make a fresh start. I regard Zen practice is discipline to notice how that letting go and fresh start is happening all the time. All the time the position of “I am” self is dissolved in a new moment of raw experience, a moment of first impressions empty of self-conscious awareness; “wiping away the karma of past lives.” Like waking to a morning bird song, that first moment before either “song” or “bird” or even before the idea of “me listening” comes to mind. It is a moment that is all-inclusive, “nothingness” in the sense of no distinctions, that quickly breaks in two: “I hear a bird.” What began as a moment free of distinctions like “self” and “other” quickly becomes observed from the remove of “I am” here, it is “there”. Words represent the experience, but are removed from the experience itself. As it is said, “Words are fingers pointing at the moon, not the moon itself.” And so the desire forms to recapture that moment of letting go, that fullness of experience, empty of self and other. This, I suggest, is the motivation of repentance. We hold so strongly to self-affirmation that the idea of experiencing yourself as ‘nothingness’ seems frightening. But isn’t it the case that both birth and death are who we are? Buddhism points out that the arising and dissolving of self is happening all the time. We are said to “wake up” to this truth as one awakens from sleep to realize something that was present all along. Buddha, the awakened one, is also called “Tathagatha,” meaning “thus come, thus gone.” Self is born out of the emptiness of raw experience and dissolved over and over again, activity explained by analogy to the natural and ordinary act of breathing. To become preoccupied with the born self, that declares “I am,” to get ’stuck’ there, to get stuck in the world or words, is the recipe for what Buddhism calls “suffering;” the “bad karma” Huineng refers to. Zen teacher Joshu Sasaki explained karma as “the activity of impermanence.” Inevitably, the born self encounters negation. Inevitably, who we are is both life and death. To stand in the way of the natural activity of coming and going, of affirmation and negation, is to stand in the way of the activity Buddhism calls Dharma, inclusive of both affirmation and negation. The posture and assumptions of self-interest are strong and deeply ingrained, deep as the desire of parents that their children will be happy and do well, reinforced by the institutions and roles society requires. Self and its needs inevitably arise, and are required by our participation in society. We want to cross the street safely. Yet to fixate a self-centered position becomes a problem. The need to negate that position is nothing less than the desire to know what is true about a universe that is, after all, not organized to accord with our preferences; to embrace with “true (selfless) love” the world in all its beauty and ugliness. A year, like that momentary experience of the singing bird, reaches a point where it, too, becomes an object of attention. Then we look at the year from the standpoint of the “I am” self, and give names to what has happened. But, I suggest, as with the singing bird, the truth of our experience is more than words, more than an idea, inspiring us to repentance, to letting go of fixation on an “I am” perspective. Like chanting the four vows. Beings numberless, liberate. Look back, reflect. But then, know that as soon as we stand in opposition to the past, and fixate that position of self and its preferences, afflictions arise. Chant. Experience yourself as nothingness. And, by nothingness, know the vow to overcome suffering, “to throw yourself completely into life and death, good and evil, beauty and ugliness." To throw yourself completely into the mystery of what lies before us, this fresh start, this new year. 11/1/22 Commentary by Gendo

“The perfect way knows no difficulties except that it refuses to make preferences.” (Shinjinmei, 7th century poem of Zen ancestor Sosan) To live is to have preferences. And who is it that has those preferences? It is of course this being we call ‘self.’ I think it's fair to say that ‘self’ is defined by preferences. We come to know who we are by our likes and dislikes. We are born on the day of our birth, but ‘self’ is born as a matter of consciousness. Parents work hard to instill the language and sensibility of who we are, the tools we need to function in society. We come to think of the conscious “I am” self as who we are. To fixate that “I am” self, is also to fixate the world of its perception, a world viewed from the standpoint of self and its likes and dislikes (“materiality”). We become so accustomed to our preferences, and to the materiality of our perceptions, that it is hard to imagine “no preferences.” Yet, it's also the case that we come to experience the ‘imperfection’ of our preferences. Just because I have a preference doesn’t mean that I get what I want! Just because I once ran a mile doesn’t mean I always can. Just because I love someone doesn’t mean they’ll never die. By such disappointments we are moved to explore what is ‘true.’ I regard Zen practice as discipline to engage in that exploration. We come to understand, it’s not “all about me;” the message of the Buddhist “wake up call” known as the Four Noble Truths. It’s also Sosan’s message: pay attention, know a truth beyond preferences. Know a truth beyond the assumptions of this identity called ‘self’ and the material world of its preferences. As I see it, Sosan’s poem is offered as a guide on that journey. The object is an object for the subject. The subject is a subject for the object. ( Lines 53,54) ‘Subject and object’ are terms used by Zen teacher, Joshu Sasaki, whose teachings inform this translation of the Shinjinmei. (Available at <uvzc.org/study-texts>.) In my view, ‘subject and object’ are other words for “preferences,” another way of describing how consciousness works. All objects of our senses, all objects of thought, are rooted in preference, in an act of comparing one thing to another; also called “dependent origination.” An object is said to be “dependent” in that it is always known relative to something else, something else described as “subject.” ‘Subject and object’ can describe any two things known relative to each other- like in-breath and out-breath, two distinct activities, nonetheless dependent on each other. You can’t have one without the other. When you breathe in, in-breath is the ‘object’ of attention. Yet that awareness stands in distinction to out-breath, the ‘subject.’ When in-breath comes to an end, out-breath wakes and now becomes object relative to in-breath as subject. Other pairs illustrating this principle are countless: day and night, mother and father, cause and effect, coming and going, life and death. There’s no end to the list. It is how consciousness works. Who distinguishes object from subject, one preference from another? Again, it is, of course, the ‘self.’ Sometimes ‘subject’ is understood in our culture as “self” in distinction to an “object” other than myself. But Zen tradition concludes that “Self” is the one who stands in the middle, between subject and object, distinguishing one from the other. Awareness of “self” is born together with subject and object, born in relation to our preferences. Know that the relativity of the two Rests on one emptiness. In one emptiness the two are not distinguished And each contains in itself all the ten thousand things (lines 55-58) The poem suggests that to know the relativity of subject and object is already to sense a truth beyond fixation on preferences, beyond our ‘hang-ups’ and our suffering. If those things that we fixate as real only exist relative to something else, then the true situation is both subject and object. When subject and object are joined, the space between them disappears. Consequently, the meeting of subject and object is the dropping way of ‘self’ and its preferences. This is oneness (“three becomes one”) and also emptiness, empty of distinctions between subject and object, empty of a separate self, empty of distinctions between this and that, timeless and inclusive of the ‘ten thousand’ (all) things. We have preferences. Self, as a matter of consciousness, is born. One becomes three. And self, as a matter of experience, disappears. Three becomes one. Both life and death are who we are, which, after all, is a teaching older than Buddhism called … Halloween - a paramita The trees Have lost their leaves, Frost has killed the garden. Gather potatoes Onions and carrots, Stash and horde because Who knows what lies ahead. Now the dead rise up And remind us Of their fate. Specters of Sawain At the door The goblin, The skeleton, The politician Avoid them Hide in darkness And they will Play their tricks Tricks are averted By one measure Give of yourself And death transforms Into something ordinary Like the kid next door. Fall arrives, impermanence arrives, announcing itself in bright colors across the landscape; showing up as dead squash vines in the garden; and the dying light of the year: longer nights, colder days. Impermanence, celebrated in the ritual we call Halloween, sends goblins and the skeletons of death to our doors, like koans. How will we answer? Turn out the lights and hide, and they will play their tricks. Can we instead, like the poet Rumi, be a guest house: this porch, this door, this house, ourselves? “Be grateful for whoever comes because each has been sent as a guide from beyond. “ This fall we have been studying the poem ‘Shinjinmei,’ written 1400 years ago by Zen monk Sen Tsan, who, like Rumi, would have us open the door and welcome whoever comes. No preferences. “The Perfect Way knows no difficulties, except that it refuses to make preferences.” And, “Try not to seek after the true. Only cease to cherish opinions.” Again, no preferences. The poem doesn’t say, never have opinions. Just don’t cherish them! Of course, all living things have preferences. Preferences are not a problem, except that they become “cherished,” fixated as some absolute, a condition Buddhism calls ‘ignorance,’ the cause of suffering. It’s called ignorance, because all form, all things, are impermanent. Zen tradition offers this explanation: Objects of our senses lack fixed identity because “knowing” always arises in contrast to something else: dark versus light, cold versus warm, red leaves versus green leaves, dead gardens versus live ones. The one who distinguishes one thing from another is, of course, the “self.” Self and its preferences give rise to form; and, at the same time, give rise to the form we call “self”. Just as all things are empty of fixed identity, the true nature of “self” is likewise empty. This is not theory. It is experience. Isn’t it the case we experience “true” generosity, “true” compassion, as having the quality of “selflessness?” Yet, the world of our preferences also happens. Self, as matter of consciousness, is born, experiences suffering, and is led beyond its preferences to the truth of its dissolution. Our true nature is both our coming and our going, both life and death. Impermanence is the goblin on the porch, the skeleton at the door. But impermanence is also candy, the face behind the mask, the kid next door, your own child. Implicit in the death of the garden is its moment of abundance, Implicit in the cold and dark is summer’s sunlight. Implicit in grief is the joy of having known someone. Zen teaches that it is our deepest desire to know both our coming and our going, to experience “true,” which is to say, “selfless,” love. Text:

“Mind is like the void in which there is no confusion or evil, as when the sun wheels through it shining upon the four corners of the world. For, when the sun rises and illuminates the whole earth, the void gains not in brilliance; and, when the sun sets, the void does not darken. The phenomena of light and dark alternate with each other, but the nature of the void remains unchanged. So it is with the Mind of the Buddha and of sentient beings. If you look upon the Buddha as presenting a pure, bright or Enlightened appearance, or upon sentient beings as presenting a foul, dark or mortal-seeming appearance, these conceptions resulting from attachment to form will keep you from supreme knowledge, even after the passing of many eons as there are sands in the Ganges. There is only the one Mind and not a particle of anything else on which to lay hold, for this Mind is the Buddha. If you students of the Way do not awake to this Mind substance, you will overlay Mind with conceptual thought, you will seek the Buddha outside yourselves, and you will remain attached to forms, pious practices and so on, all of which are harmful and not at all the way to supreme knowledge.” (The Zen teaching of Huang Po) Commentary by Gendo I regard ‘fullness of mind’ as the big picture of what is involved in this activity called “consciousness,” the activity of mind. I often talk about how Zen analizes consciousness; and concludes that every act of conscious awareness involves a dualism, an act of discrimination, contrasting one thing with another. Like the contrast of light and dark Huangpo refers to in our text. Like pure and foul. Like any duality we might generalize as ‘plus’ and ‘minus’. We know plus in contrast to minus, and viceversa. What from the viewpoint of Huangpo’s void, or outer space, is seen as a dynamic whole, earthlings divide into day and night. And the one who arises between those two, and discriminates one from the other according to its preferences, is the self. In this fashion, Zen theorizes that the activity of discriminating consciousness is the activity where ‘one’ breaks apart and becomes ‘three:’ plus, minus, and self. The analogy is to birth, to the union of a man and a woman, and the birth of the child, the self, that stands between them, and regards them apart from itself, and apart from each other. But this is an incomplete perspective; or what in Buddhism is decribed as “relative truth.” As a matter of experience, we know the incompleteness of that perspective. We have a sense that it is not the whole truth. Like coming away from a really great movie, where you have lost yourself in the plot and characters, and, for a moment, you are living that world, and don’t even want to talk about it, because to talk about it feels like you have left it. Huangpo points out that the big picture is day and night together, one dynamic activity, without separation. Purity and foulness are like this. Plus and minus are like this. All dualities are like this. When separation between them disappears, when object consciousness disappears, the self that discriminates one from the other disappears. The big picture is light and dark, pure and foul, plus and minus, together in one dynamic activity, free of a separate self and its preferences. This is the state in which three (father, mother and self) become one family; an experience Buddhism describes as an “absolute truth;” an experience of ”blowing out,” like blowing out a candle, the blowing out of the candle of separate identity. The ancient Sanskrit word for that blowing out is “nirvana.” But even this absolute truth is not a fixed thing. The separate self disappears into the wholeness of the family, but soon a new self identity is born: my family as opposed to other families; my town versus other towns, my school versus other schools, my country versus other countries, my ethnic group versus others, my Buddhism versus your cellphone app. Over and over again, three becomes one, one becomes three. Yet there is progression. We call it maturity; the maturity to rediscover the absolute within the relative over and over again with each expanding dimension of life. Sasaki Roshi said it this way: “The way the child first appears is to receive both plus and minus in equal amounts. But what will this born child eat? Just to say it simply and perhaps extremely, mother and father are what the child eats inorder to grow.” All relativity, rests in one absolute; the absolute we are born with, before any notion of a self has formed, the absolute we return to in the moment of our death, the absolute, the nirvana, inherent in every moment of conceptual thought, in the attachment to forms. In Huang Po’s words, even the distinction between “enlightened appearance,” and “foul mortal-seeming appearance” is to be let go of. Form is emptiness, emptiness is form, says the Heart Sutra Three is one and one is three. If we are going to find peace in the world, if we are going to get along with people who are different from us, we need to pay attention, awaken to “one mind.” If we are to find trust in ourselves, trust in the wisdom of ‘one mind,’ we need to know that wisdom for ourselves. This is practice. TEXT:

“You may study sitting in meditation, but meditation is not concerned with sitting or lying down. You may study sitting in Buddha, but Buddha is not concerned with any fixed form. Of all abodeless dharmas, the Buddha is not to be chosen. If you sit in Buddha you will kill the Buddha; if you cling to the form of sitting, you will not reach the principle.” (Zen teacher Huai Jang, as recorded in the “Transmission of the Lamp) What is true about meditation? What is true about anything? Zen teaches, the text teaches, that we cannot make an object of truth or God. What is ultimately true about any situation is impermanence, impermanence that cannot be captured as an existent thing, a form, a particular idea. As soon as we have fixated a particular thing and say, “This is it! This is true!” we make a mistake; a mistake because object fixation is always from the standpoint of a separate self, always from a self-affirming point of view. Even Buddhism, even Buddha, regarded as object, as something to be attained or acquired, is mistaken. All teachings, all doctrine, even the US Constitution, are like this. Objectified as truth, they become a pretext for abuse. Preoccupation with some “fixed form” is not only self-absorbed; it is also unjust; unjust because it is blind to failure, our own, and those who are most vulnerable. These are struggles that we return to again and again. We return to our self-centeredness again and again. And so we speak of diligence, the diligence to engage in practice, again and again, to face our struggles and learn from them. Learning starts with something we want, a skill or accomplishment we want to acquire. We begin with a goal in mind. But it turns out, that, in order to get there, we have to practice, and practice involves both success and failure, over and over again. It’s as if that thing or skill we viewed as success, as a plus, turns out to involve equal portions of failure, minus. With diligent practice, plus and minus combine and become zero, the zero of ‘just doing.’ With diligence, finally, there is ‘just doing’ called ‘mastery’ or ‘wisdom.’ What was conceived of as a goal to be acquired becomes ‘letting-go;’ letting-go of both success and failure, letting-go of the objective itself that has become ‘just doing.’ By diligence, by engaging success and failure over and over again, the arc of experience (to paraphrase Martin Luther King) “bends toward justice,” bends towards compassion for our own failings and for those who are most vulnerable . What was imagined from the start as something to be achieved, is instead, found inside; neither success or failure, a truth underlying all encounters of self and other. This, I suggest, is the “waking-up” we are invited to, personified as “buddha,” as God, experienced as selfless love, and the relief of suffering. |