|

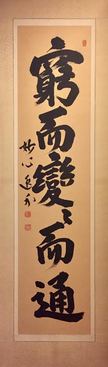

Commentary by Gendo This calligraphy by Kajiura Itsugai, former head of Myoshin-ji temple in Kyoto, Japan, hangs in our Zen Center. It was a gift of Kyonen Jim Gordon, a friend, mentor, fellow practitioner and lay ordained Zen monk. It is a quote found in the Blue Cliff Record, an ancient collection of koans, cases used to test understanding. What does this mean? One way or another, we are reaching an extreme, coming to an end, all the time. How does a person pass through? How do you live your life in the midst of change? Sometimes a big change comes along: Someone you love dies, or a relationship breaks up, or storms destroy your home, or (before long) carbon tax makes your car unaffordable; and you think, something has ended that will never happen again. Nothing I do will change this reality. How do you “pass through”? I write this at the end of the year. We will never see the year 2018 again. For better or worse, it has come to an end. Buddhist tradition explores change with attention to a basic, embodied activity – breathing. Breathing repeatedly comes to an end, reaches an extreme. Breathe out and you reach a point beyond which you can go no further. Then what? After a moment’s pause comes change, transformation, and the opposite activity, in-breath, takes over. Human beings have evolved consciousness to further their own situation. We have learned, and teach our children, to identify all kinds of objects, to know likes and dislikes, and to form an idea of self, of who I am. But Zen points out that consciousness is imperfect. It is imperfect, because everything we identify as an existent thing, including ‘self,’ is subject to change, to impermanence. They do not last and that which does not last we experience as beyond our control; and what is beyond our control, we understand to be other than myself. Everything we are taught to name and know reaches an extreme, comes to an end, regardless of our intention. If even ‘self’ is not ‘mine’ to control, where am I? Who am I? These are existential questions, the suffering, inherent in consciousness – the ‘tree of knowledge’ that Adam and Eve discover in the Garden of Eden. Buddhism teaches that the reason human consciousness is imperfect is that knowledge is an act of discrimination. We discriminate in-breath from out–breath; which is to say, we know one because we know the other. What is imperfect is the assumption that, because we have named them, each has it’s own essence, its own independent existence. On inspection, however, that assumption is mistaken. It is delusion because in-breath and out-breath, like all objects of consciousness, are discriminated, one in relation to another. The larger truth of breathing and all objects is not separateness but relationship, activity empty of separate identity, beyond conception, beyond thought altogether. That reality, like breathing, is dynamic, never fully one thing or another. It is the ‘cosmic dance’ that cannot be objectified, and yet neither is it 'nothing.' Consequently this ‘non-object’ is personified as God, or Dharma, or ‘true self,’ or true (selfless) love. How do we know such a truth? There is no object to be acquired or taught, no self to attain it. It simply is what is experienced when the mind that fixates object and identity is quiet; as in the stillness at the extreme between in-breath and out-breath, a stillness empty of distinctions, self and other, and, at the same time, all-inclusive. Potluck Lunch. Join the Board of Directors for potluck lunch, January 6, 11:30 to 1:00 at the Zen Center. All are welcome. Bring something to share. Let us know if you plan to come.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |